Profile: Betsy Jacaruso

|

By RAYMOND J.

STEINER

ART TIMES May 2009

Quince |

In my thirty-plus years of profiling visual artists — and, Betsy Jacaruso is no exception — a recurrent theme seemed to be that “something set them off” in answer to my question as to “why” one pursues an artistic career when, by most accounts, it is universally given such short shrift in a materialistic world. It was almost always stated that some thing, some person, some event, “flipped the switch”, so to speak, and it was this that put them on the path of pursuing a career in art. The beginning is often couched in terms of its being some kind of ‘epiphany’, a kind of ‘aha!’ that opened the door to inner urgings and secrets that lurked beneath the surface of day-to-day existence. For most, it was a pleasing discovery, one that they fondly recalled and often found excitement in repeating — though not so for Betsy Jacaruso.

Anemones III |

Also for most, the initial impetus comes early in life — but, again, not always. My Roman friend, Pier Augusto Breccia, for example, stumbled upon his propensity for creating images very late in life. For years Rome’s eminent heart surgeon, Pier did not discover his artistic side until well after his one-thousandth heart operation, an epiphany precipitated by strange images appearing on his notepad as he idly doodled while sitting in his office at the Catholic University Hospital. Today, no longer working as a surgeon, he is world-renowned as an artist. I attended an opening of his at the Palazzo Venezia last year to which over 3,000 people came from around the world. Conversely, Heinrich J. Jarczyk, although he came to art early in life during his youth in Silesia, had his career as an etcher/painter held up for many years by World War II. He worked as a research scientist until his retirement — at which time he turned his attention to his early love of art. Today, he also is known both in Europe and America as a master draftsman and painter. Unlike either Breccia or Jarczyk, the American artist Paul Cadmus was an early and steady evolver into full artistic maturity (calling his adolescent forays into artistic expression his “DeKooning Period”), but experiencing no significant hiatus in his artistic flow throughout his career.

After the Storm |

For Betsy Jacaruso, the ‘awakening’ came early; however, unlike so many who have found pleasure in the memory, for her the beginning was shrouded in darkness. Like many early experiences in our lives, those days have been buried in the intervening years of living and growing — and this, perhaps, is as it should be. But, for Jacaruso, they could not be entirely sublimated until she could rid herself of the lingering memories of those early years. What is important is what Betsy Jacaruso has done with those childhood experiences — and this, as we might expect in an artist, has been accomplished through her painting. Even the most cursory comparison, for example, between “Trapped”, a forbidding image of a glowing, angelic little blonde girl held on the lap and ‘embraced’ in the arms of a shadowy and sinister man with barely discernible features and many of her color-drenched florals and nature-study paintings of today, loudly proclaim the dramatic shift in her aesthetic focus. Being driven inward in the face of negative circumstances might have permanently destroyed the psyche of a lesser person — but in the case of Betsy Jacaruso, the experience turned a frightened little girl into the inner magic of another, a more creative and beautiful world — a world that transformed her into a world-class painter.

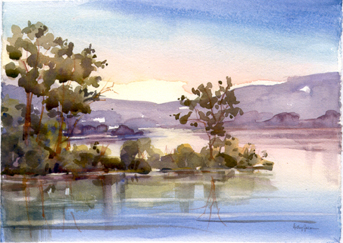

In the Cove |

Still, tapping into that inner spring of creativity is only the first step — a giant one, granted, but only the beginning of realizing one’s artistic potential. Once the desire/need to bring up those hidden treasures grows into necessity, the task of finding proper imagery in which to share it with the world is immanent — and here it is that the true artist is separated from the rest of us for it is the expression (i.e. drawing the “straight line”) that provides both direction and urgency. The non-artist simply ignores or shouts down the urge to create — the true artist becomes committed. Betsy Jacaruso was absolutely committed.

And she has indeed come a long way — not only from that time I first saw her work in the student show that her teacher, noted watercolorist Linda Novick, held at Company Hill Gallery in Kingston, New York, over a dozen years ago, but from a past that threatened to devour her. The coerced inward journey into herself proved to be not only an escape from being ‘trapped’, but a clear path beneath the surfaces of things, a slowly-widening avenue into that bright, spiritual core that comprises our creative fount. If Betsy Jacaruso discovered her aesthetic resources, she also discovered a world where the hidden essence of nature was revealed to her. If such beauty could reside in the darkest of places, what might she not find in the world around her? She discovered that it was not merely what we saw — or even what we might experience — but the underlying nature of the phenomenal world — what German aestheticians called das ding an sich (“the thing in itself”)— that we ought to uncover — for it is here that the wonder and beauty of our world exists.

Anemones in Yellow |

Once her foot was placed firmly on the path of aesthetic discovery — and this took years of perfecting her draftsmanship while closely observing nature both here and abroad — she could now turn to passing on that gift to others. Once she saw what her painting was doing for her, she opened her first workshop in — what could be more appropriate? — a garden center in Rhinebeck, New York, called the “Phantom Gardener”. From this tentative leap into the public arena, Betsy Jacaruso has blossomed (a word perhaps also appropriate here) into both a sought-after artist and teacher. As passionate in her teaching as she is in her painting, I asked her how she passed along her secrets of finding one’s way into the elusive inner self to her students. “I see myself only as a ‘facilitator’,” she replied. “They must find their own inner sources.”

Purple Clematis |

‘They’ obviously do, since her popularity as a teacher continues to grow. I experienced some of this at first hand — both her relationship with her students and her standing in the arts community — at an opening of her Annual Students Show in April. To begin with, I have attended a great many art receptions in New York State’s Hudson Valley and few that I can recall were so well-attended as was her student show. The easy give-and-take — along with the real affection that freely flowed from student to teacher in the face of a public event, showed the genuine solidarity that exists between Betsy Jacaruso and her students, a fact borne out on the walls of her studio (The Betsy Jacaruso Studio & Gallery, an airy, light-filled space in a building called ‘The Chocolate Factory’ located in Red Hook, New York), since one could easily trace just how influential a teacher she is. Many of her students indeed seemed to be discovering their own inner resources. Where she — and her art — comes from, makes her a seriously determined artist/teacher; what she has discovered in the process, transforms her into a buoyant, positive, and caring human being that invites genuine emulation.

Le Lodole |

Betsy Jacaruso’s space —both inner and outer — today allows for little evidence of ‘phantoms’, but rather a world exposed to full light — light that is both natural and spiritual — for there is no more fitting description than ‘spiritual’ for many of her paintings. This is especially evident in her current series of glowing anemones (“Anemones in Yellow”, “Anemones III”, to name but a couple) though there is as much light and magic in such landscapes as “In the Cove” or “Olana” (among a great many others you might choose as exemplars) — and even in an untitled, tonal black and white watercolor! Tucked away in a back room of her studio where she took me to browse through a sketchbook or two, we uncovered a few more such drawings and paintings as “Trapped” — and, though bubbly and pert by nature, it is obvious that the pain is still revealed in her eyes as she is confronted by memories of those early years — but the glorious profusion of colorful florals and landscapes in the front room bespeak just how far Betsy Jacaruso has come in her artistic journey.

Betsy Jacaruso Working Inside Her Studio /Gallery |

Today, her paintings garner awards, honors, exhibitions and patrons across the United States — a reputation that will surely soon extend abroad as her painting excursions to such places as Tuscany and Burgundy expand and continue. Souvenirs of her travels such as “Villa Toscana”, a large watercolor sketch of a sun-filled garden outside a home surrounded by purple hills in the Italian landscape, will deepen in intensity and complexity as she delves under the surface in foreign climes — as she has done here in the landscapes of her home in the Hudson Valley. And, as she continues to uncover the secrets of a setting sun, a pastoral vista, or a single anemone bloom, so shall she continue to show us all the magic of being.

(A full résumé and more of Betsy Jacaruso’s work and can be found at www.betsyjacarusostudio.com)